There was a knock at Tim’s front door. Impossibly, there was a knock on a day there shouldn’t have been one. Not that it was a big disturbance, it had only interrupted his woolgathering. He began reading a book hours ago and somewhere along the way his mind drifted off to the point where he wouldn’t have been able, even with a gun pressed to his temple, to tell which page he was on or what part of the story he last read.

The knock again. Tim placed the book open face down on the side table. Next to it was the handheld trigger for the silent alarm which he picked up and let his thumb hover over the panic button. Should he press it or simply answer the door? Smart money was on activating the alarm but he had always been a slave to curiosity so he pocketed the remote, rose from his comfy chair, exited the living room and padded across the hardwood foyer floor on the balls of his feet.

The closer he got to the door he heard some sort of commotion going on outside and as his hand landed on the doorknob he drew in a deep breath and held it for a long moment to quell the anxious feeling hatching in the pit of his belly. Tim hadn’t realized just how unaccustomed he was to answering his own door, it had been so long.

As he turned the knob a thought crossed his mind, perhaps the person on the other side of the door, the lawbreaker, was a deranged lunatic or religious fanatic who saw it as their duty, their purpose, their God-given right to put an end to what they viewed as an abomination. He knew that wasn’t the case, though. The knock was far too polite. They were all so damned polite, the knockers. Lightly rapping on his door all day, all night, in any weather, even on holidays. Especially on holidays. The only time they didn’t knock was on Sunday, his sanctioned day of rest.

He opened the door to shouts and protests. A crowd of people clustered on his front porch began forming a semi-circle behind the woman who stood in the doorway directly in his face. They accused her of jumping the queue, shouted that what she was doing was illegal, and warned/threatened her with the prosecutable penalties of her actions. And the discontent was spreading along people of all ages, ethnicities, male and female alike who gathered in a line that ran the length of his front walk to the pavement, down the block, and most likely around the corner, who were waiting their turn for an audience. But all the chatter came to an abrupt halt the moment they caught sight of Tim.

The woman in front of him, the illegal knocker, had a familiar face but her features were too average, too face-in-the-crowd, to recall outright, Tim had to flip through his mental rolodex and play the association game. He twigged her face was connected to some sort of event that would have revealed a location that eventually would have produced a name. Taking a deep breath, he relaxed his mind and softened his focus and let his gears spin a bit until he came up with:

Fundraiser ~~> community center ~~> Dick Cole

This woman was a friend of Dick Cole. Linda something-or-other. Rhymed with seed. Greed? Mead? Plead?

“Linda Reid,” Tim smiled, more at the swiftness of the connection than the pleasure of seeing the woman. “It’s been a while. A couple of years, I think.”

“Settle down, everyone,” Tim addressed the throng beyond the woman. “You know I’m not allowed to accept appointments today so she’s not cutting in line ahead of any of you. She happens to be a friend.”

Tim gestured for Linda to step inside which prompted the grousing to recommence but he merely closed the door to let them vent amongst themselves.

“Sorry for causing a commotion,” Linda said, smiling a bit too much. “And for not keeping in touch. Things have been so hectic down at the center with budget cuts and understaffing…and other things, that I don’t socialize much anymore. And you’ve got a lot on your hands at the moment—”

Tim waved off the rest of the sentence. “No worries,” he said, leading her past the empty administrative desks and into the sitting room.

“Awful lot of furniture crowding your foyer,” Linda said.

“That’s for the staff, doormen, greeters, admin assistants, all government appointed. They see to visitors. There are also bodyguards posted at each of the house’s ingress and egress points but they all have the day off because it’s my day off.”

“I suppose that’s another thing I’m sorry for.”

“I don’t get many non-work related visitors so this is a welcomed change,” Tim said, gesturing for Linda to take a seat. “Can I get you anything? Water? Juice? Or I could put the kettle on?”

“Do you have anything stronger?” Linda asked sheepishly as she sat down.

“I don’t imbibe, I’m afraid. Rules of my employment and all.”

“Yes, of course, how foolish of me. Water’s fine, then.”

Tim popped into the kitchen and returned with two glasses and ice water in a silver pitcher dotted with dew-like condensation.

“Not to fret,” he said, sitting opposite Linda and filling her glass. “Most people never consider it when they drop by.”

She took the water glass and swallowed two gulps. “I–um–I think I have a slight confession to make.”

“This isn’t a social visit, is it?”

“I can explain.”

“Explain what exactly? That you’re a lawbreaker and you seek to make me complicit in your crime? Is this a trap? Did the organization send you? Are you here to test me? Well, I’m not having it so you can go back and tell your bosses that I don’t cut side deals to pocket a little extra cash. We made an arrangement and I’m honoring it to the best of my ability!”

“So, how does this go? Do I have to fill out an application? Sign a legal document? Do you need proof? I didn’t think to bring any with me but I can get whatever it is you need.”

“If your request is granted, you’ll need to sign a few documents, including one that absolves me of any blame should the outcome fail to have the desired effect,” he said automatically.

“Naturally, without a doubt,” Linda answered, a bit too eagerly.

They’re always so eager at this stage, before the harshness of reality sets in, Tim thought. “But for right now, all you have to do is tell me what brings you here.”

“Um, okay,” she adjusted herself in the seat and wondered how her breath could so suddenly get caught in her throat. “It isn’t for me, you understand, I’d never come to ask for myself.

It’s my fiancé, Dick, you’ve met him, in fact, he introduced us at a fundraiser two years ago.”

“Yes, I know Dick. What’s wrong with him?”

“He has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” Linda said in a quiet voice.

“Lou Gehrig’s disease.” Tim’s stomach turned over. He didn’t need her to elucidate further.

She nodded, her eyes fading down to the throw rug, absently tracing patterns. “It’s in the late stages now. I would have come sooner, but it’s taken me some time to talk Dick into this. He doesn’t think it seems right. Not what you do, that’s fine and he thinks you’re a saint for doing it. He doesn’t think it’s right asking you for help, especially this kind of help. Dick doesn’t want you or anyone else taking pity on him. He’s never taken a handout in his life and he can’t help but see this as charity.”

“Yes,” Tim said, not bothering to hear the rest of the pitch. That’s what they were, pitches. Not simple requests or implorations, these were stories designed to pull at his heartstrings. But who ever bothered to listen to his story? Not one of them. Not a single person among the many that crossed his threshold ever bothered asking him a personal question. As if he wasn’t human, as if he wasn’t allowed his own tragedy.

“What? I don’t understand.” She set the glass down on the nearby table, missing the coaster by half an inch. Tim either hadn’t noticed or decided not to comment.

“I’m saying, yes.”

“Yes, you’ll help?” Linda blinked and met the man’s gaze as a hopeful smile began to split her face.

“Yes.”

“I — I don’t know what to say,” she was on her feet before she knew what was happening, moving in for a hug. “I — thank you, Tim!”

Tim put his hand up, stopping the woman in her tracks. “Don’t thank me yet. There are still a few things you need to realize before you accept my offer.”

“It doesn’t matter. Anything! And I mean anything!” Interest colored her face.

“Please calm down for a moment and listen to me. This thing you’re asking of me, this gift of blood, it may not solve your problems and could possibly worsen matters for you.” Tim traced his finger around the rim of his glass.

“I’ll take that chance… we’ll take that chance!”

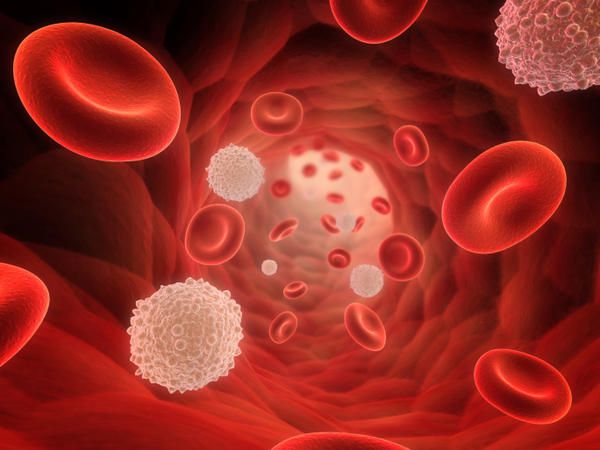

“Listen to me!” Tim brought the glass down on the table, just hard enough to startle and capture her full attention. At the cost of a wet sleeve and the water stains that would surely mark the cherry wood. “Ever since scientists discovered the curative properties of my blood, tests have been run. Mostly successful, I’m a match for all blood types, and my white blood cells haven’t encountered a disease it can’t cure—”

“Which is why I came to you. I did my research and you cured other ALS patients before—”

“The problem isn’t my blood,” he interrupted. “It’s Dick’s immune system reaction that’s the danger. If his body rejects my blood and tries to attack parts of it, there won’t be a second chance. He instantly becomes a non-match. On the other hand, if his body takes the transfusion, in a few month’s time, his white blood cells will resemble mine and he’ll automatically be enlisted in the same line of work as I am.”

The weight of Tim’s words slowly settled on Linda. “You mean, he’ll—?”

“He’ll never know another moment’s peace for the rest of his life. People will hound him, pleading for themselves or family or friends, day and night, night and day. Nonstop. Some gentle, others less so.”

“But why is that necessary?” Linda asked.

“My white blood cells can’t be synthesized. Top minds have tried and failed time and again. And although my blood can be stored, the white blood cells lose their miraculous properties over a period of thirty-six hours outside my body.

“I would have been strapped to a table in a laboratory for the rest of my natural life if I wasn’t for my brother. Hell of a lawyer. Fought his ass off to petition the quality of life rights that allow me the tiny bit of freedom I have. The stipulation is I must share my gift, triage the world, help the sickest among you. There are restrictions, legal hours when people have the right to approach me, but no one listens. How can they be expected to follow the rules when they or their loved ones are dying?

“I used to fight it. Turn people away when the established workday was through. Dealt with the angry mobs and the death threats. Then I asked myself, “Why?” Why fight my fate? If I’m meant to help people, why shouldn’t I do it when it needs to be done and not only when I want to do it? And there’s a selfish reason if I’m honest. You see, if I help enough people, if enough of the populace possesses my blood, I won’t be special anymore or alone in all this. Maybe then, when there’s enough blood to go around and my bit for the world is done, the price of my gift paid, maybe then I can be left alone to die in peace.”

Linda hesitated. She shook her head and turned to leave. “This… this is… “ She stumbled over the words, not knowing how to express her thoughts.

Tim realized too late that he said too much, chose the wrong person to unburden himself on. He regretted his action instantly. “It’s a lot to process, I know. Why don’t you go home and discuss it with Dick? You can contact me if you decide to go through with it.”

From his shirt pocket, he fished out a solid white business card, imprinted only with a faint phone number that had to be viewed at the proper angle in order to be seen. “A direct line, please don’t share it with anyone.”

“I won’t,” Linda muttered as she shambled to the doorway. “I — look, I know you can’t talk about the other people you’ve seen, but can you just tell me if anyone has ever turned down your help after you’ve explained everything to them?”

For a moment, Tim didn’t respond, he just watched as the hope drained from her face. “More people than you might imagine.” He noted she found no reassurance in his answer. He turned away, unable to look upon her sorrow any longer. He had his own to contend with.

Over his shoulder, he said, “Be sure you tell Dick everything I’ve told you, and if he refuses, try to understand. Sometimes there are worse things than death.”

Text and Audio ©1988 – 2021 Rhyan Scorpio-Rhys